NREM SAF Program Overview

The Department of Forestry at Oklahoma State University was formed in 1946 with Dr. Glen Durrell as Department Head and 3 faculty members, Dr. Michel Afanasiev, Dr. Nat Walker and Mr. Edward Linn. The Department was first accredited by the Society of American Foresters in 1971. The Forestry Department was merged with faculty from other departments to form the Natural Resource Ecology and Management (NREM) Department on July 1, 2006. The NREM faculty consisted of the forestry department faculty, five wildlife and fisheries faculty from the Department of Zoology, five rangeland ecology faculty from the Plant and Soil Science Department, and two USGS scientists from the Oklahoma Wildlife and Fisheries Cooperative Research Unit. Because of the transition of the Forestry Department into a new department, the SAF granted an extension of accreditation review until 2008. The NREM Department offers 5 undergraduate options: Fisheries and Aquatic Ecology (FAEC), Rangeland Ecology and Management (RLEM), Wildlife Ecology and Management (WLEM), Wildlife Biology and Pre-Veterinary Science (WBPV), and the SAF-accredited Forest Ecology and Management (FOEM). The last site visit for SAF re-accreditation of FOEM option was in 2018 when this option was re-accredited.

NREM Educational Objectives

The educational objective of the NREM Department is to prepare our graduates for productive professional and personal lives. This requires developing professional/technical competencies, communication and quantification skills, analytical and problem-solving skills, and effective interpersonal abilities that support a strong sense of professional and ethical values. The Department maintains seven long-term strategic objectives that allow it to adjust and grow, continuously meeting the changing needs and demands of Oklahoma citizens and the world:

- Conduct research on the organisms, components, and processes of a diverse array of natural ecosystems in Oklahoma and beyond and generate knowledge to apply to the management of these ecosystems.

- Develop inter-disciplinary, systems approaches that facilitate management of natural resources for sustainable agricultural and forest production and maintenance of ecosystem health.

- Maintain high quality undergraduate and graduate programs in fisheries, forestry, rangeland, and wildlife ecology and management.

- Maintain a high quality SAF-accredited undergraduate professional forestry degree program through interdisciplinary instruction and experience from the entire NREM faculty

- Involve undergraduate students in research activities as outlined in Objective 1.

- Enhance existing and develop new innovative Extension and outreach programs that provide stakeholders with the knowledge to make informed decisions regarding management of natural resources, including application of technologies for preservation, conservation, sustainable use, and/or restoration of natural resources.

- Foster broad understanding and public appreciation of natural resource conservation and management through collaboration with related disciplines.

The integration of forestry, fisheries, rangeland, and wildlife into a single department demonstrates the commitment for an interdisciplinary approach to education. While there is considerable discipline-specific knowledge that must be taught, each of the disciplines in the NREM department understands and appreciates other aspects of natural resource management. It is important to the NREM faculty that students be well rounded in natural resources issues and knowledge, while maintaining a strong disciplinary base.

Our NREM Mission is: To increase public awareness and understanding, through teaching, research and Extension,

of the ecology, management and sustainable use of natural resources that are important

for maintaining ecosystem health, species diversity, agriculture and forest production,

hunting and fishing, and the enjoyment of experiencing nature in Oklahoma and beyond.''

SAF Guidelines Concerning Program Mission, Goals, and Objectives

SAF accreditation standards specify the technical, professional, and interpersonal skills needed for a successful career in forestry. NREM fully supports these standards and the 7 objectives listed above demonstrate a strategic level support for the SAF guidelines, some of which are highlighted here:

Meeting Diverse Social, Cultural, Economic, and Environmental Needs and Values

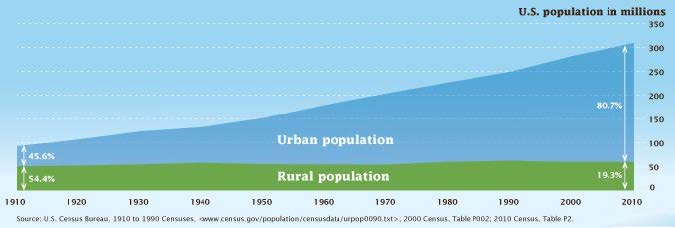

A population shift from rural to urban centers has been underway for decades throughout the United States (Figure 1). The urban population is now larger than the rural population in many states, including Oklahoma (Table 1). In Oklahoma, pre-dust bowl populations in 1930 were two-thirds rural and one-third urban. Those percentages were reversed by 2010, with the dust bowl devastation of rural populations between 1930 and 1950 contributing to that conversion. Interestingly, in 1950, the urban/rural population distribution in Oklahoma was 50/50.

Figure 1. Urban and rural population count in the U.S., 1910 to 2010.

More recently, urban populations grew at a faster rate (10.2%) than rural populations (5.9%) from 2000 to 2010. While the percentage of the population in 2010 that is rural remains greater in Oklahoma (34%; Table 1) than nationally (19%; Figure 1), there is no question that demands from forested lands in Oklahoma will continue to change and students must be prepared to understand and manage new challenges, especially as urban and suburban interests impact resources on rural lands. An additional critically important factor is that all of Oklahoma’s commercial forested land is located in close proximity to the Dallas/Ft. Worth urban area in Texas, and urban dwellers from north Texas increasingly view southeastern Oklahoma as a recreational area. All of these concerns are addressed by Objectives 1, 2, 6 and 7 listed above.

| Census Year | Urban Population | Percent Change | Rural Population | Percent Change | Percent Urban | Percent Rural |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1910 | 318,975 | - | 1,338,180 | - | 19.2 | 80.8 |

| 1930 | 821,681 | 157.6 | 1,574,359 | 17.6 | 34.3 | 65.7 |

| 1950 | 1,107,525 | 34.8 | 1,126,099 | -28.5 | 49.6 | 50.4 |

| 1990 | 2,049,987 | 85.1 | 1,095,598 | -2.7 | 65.2 | 34.8 |

| 2000 | 2,254,563 | 10.0 | 1,196,091 | 9.2 | 65.3 | 34.7 |

| 2010 | 2,485,029 | 10.2 | 1,266,322 | 5.9 | 66.2 | 33.8 |

Response to the Needs of our Clientele and Stakeholders

The clientele and stakeholder base and our ability to address multiple issues have become much broader than in the past. In addition to commercial timber production and land management agencies, the current clientele base for the NREM department includes owners of small non-commercial land holdings, specialty product manufacturers, ranchers, hunters, recreational users, and urban dwellers. Many of our forestry faculty and students are involved in stakeholder outreach programs. These values are reflected in Objectives 1, 2, 6 and 7 listed above.

Maintain Professional and Ethical Behavior for Forest Management

To be an effective voice for natural resources, our students need a sound scientific education but also need professional integrity and ethics. Our department emphasizes professional and ethical behavior in our courses and in continuing education. The University places high priority on academic integrity that is stressed in the syllabus of each departmental course. While the NREM department does not list ethical behavior in any of the strategic objectives listed above, the department fully adheres to the ethical standards developed and cultivated at the university level.

Summary of Oklahoma’s Forest Resources

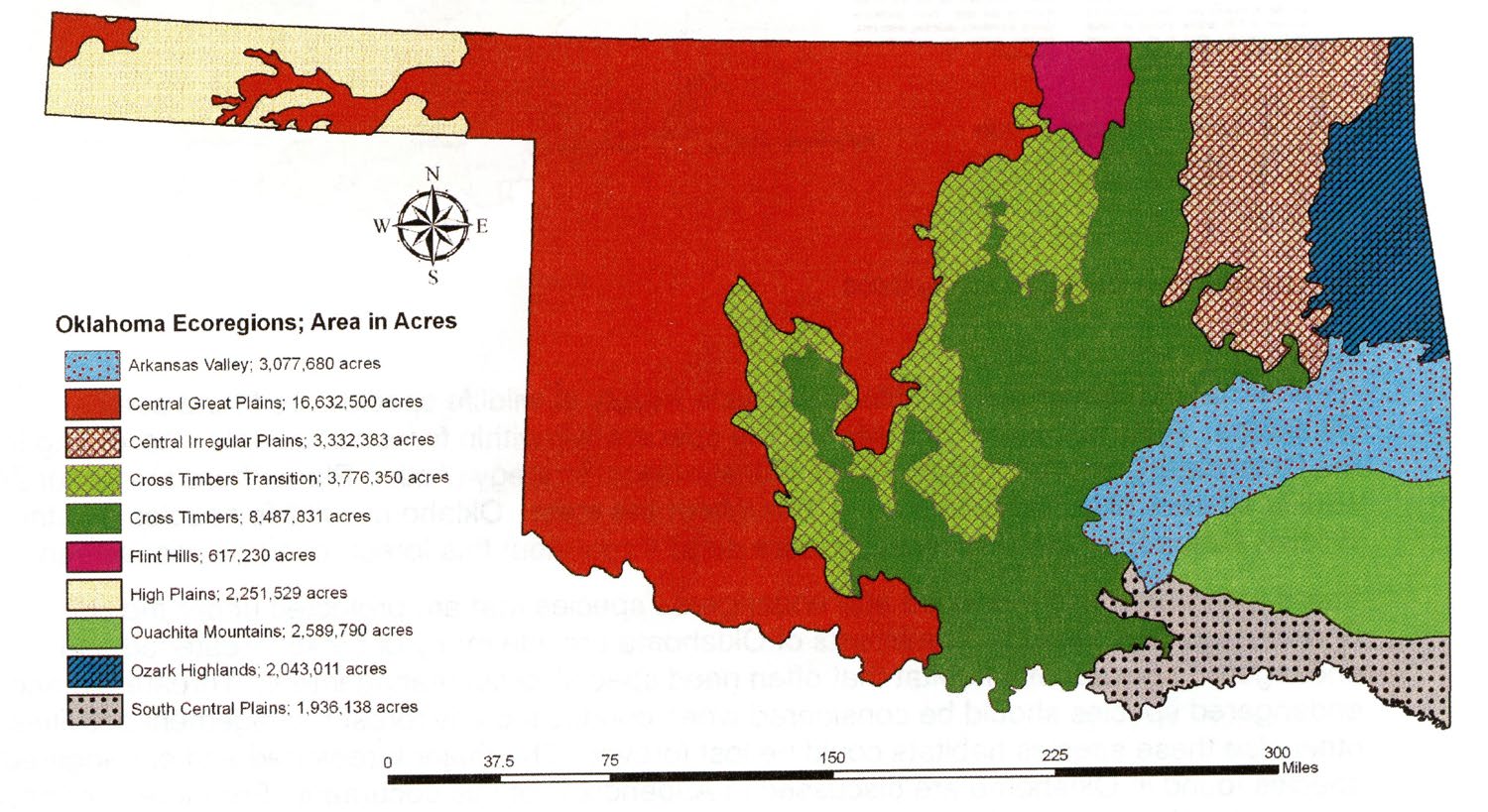

Approximately 40.5%, or 18.1 of Oklahoma’s 44.7 million acres includes ecoregions that have the potential to support forests. These include the Arkansas Valley, the Ouachita Mountains, the South-Central Plains, the Ozark Highlands, and the Cross Timbers (Figure 2 and Table 2). While the remaining 5 ecoregions in Oklahoma, the Cross Timbers Transition, the Central Irregular Plains, the Central Great Plains, the High Plains and the Flint Hills, do contain some forest cover, they are classified as having originally been savannas or rangelands, although much of this country has been converted to crop land.

The oak-pine forests of southeastern Oklahoma, which include the Arkansas Valley,

Ouachita Mountains, and South-Central Plains regions, make up about 18% of the land

area of Oklahoma, or 7.6 million acres (Table 2). These regions are dominated by native

shortleaf pine (Pinus echinata), black oak (Quercus velutina), white oak (Q. alba),

northern red oak (Q. rubra), post oak (Q. stellata), blackjack oak (Q. marilandica),

water oak (Q. nigra), willow oak (Q. phellos), mockernut hickory (Carya tomentosa),

bitternut hickory (C. cordiformis), and winged elm (Ulmus alata). While loblolly pine

(Pinus taeda) is only native to the southern half of the southeastern most county

(McCurtain Co.), approximately 1 million acres are managed as loblolly pine plantation,

primarily in the South-Central Great Plains and Ouachita Mountains regions.

Figure 2. Ecoregions in Oklahoma (from Oklahoma Forestry Services (OFS), 2010, Oklahoma Forest Resource Assessment, page 13).

The Ozark Highlands ecoregion, also known as the oak-hickory forest, comprises 2.0 million acres in northeastern Oklahoma (Oak-Hick in Table 2). It represents the western edge of the eastern deciduous forest, with species characteristic of the Ozark Plateau, and its distribution coincides primarily with the Ozark Plateau Physiographic Province. Forest species that occur in this region include black oak, white oak, northern red oak, post oak, mockernut hickory and bitternut hickory. Pockets of shortleaf pine are also present.

The Cross Timbers region, distributed in a north-south swath across the center of

the state, makes up 8.5 million acres, or 19.0 % of the land area of Oklahoma. The

dominant tree species, post oak and blackjack oak, are mixed in a mosaic with tallgrass

prairie grass species and non-commercial woody plants.

| Ecoregion | Land Type | Acres | Grouped Acres 1 | % of State Total | Grouped Acres 2 | % of State Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arkansas Valley | Oak-Pine Forest | 3,077,680 | 7,603,608 | 17.0 | 18,134,450 | 40.5 |

| Ouachita Mountains | Oak-Pine Forest | 2,589,790 | ||||

| South Central Plains | Oak-Pine Forest | 1,936,138 | ||||

| Ozark Highlands | Oak-Hick Forest | 2,043,011 | 2,043,011 | 4.6 | ||

| Cross Timbers | Forest/Savanna | 8,487,831 | 8,487,831 | 19.0 | ||

| Cross Timbers Transition | Savanna | 3,776,350 | 7,108,733 | 15.9 | 26,609,992 | 59.5 |

| Central Irregular Plains | Savanna | 3,332,383 | ||||

| Central Great Plains | Grassland | 16,632,500 | 19,501,259 | 43.6 | ||

| High Plains | Grassland | 2,251,529 | ||||

| Flint Hills | Grassland | 617,230 | ||||

| TOTAL | 44,744,442 | 44,744,442 | 100 | 44,744,442 | 100 |

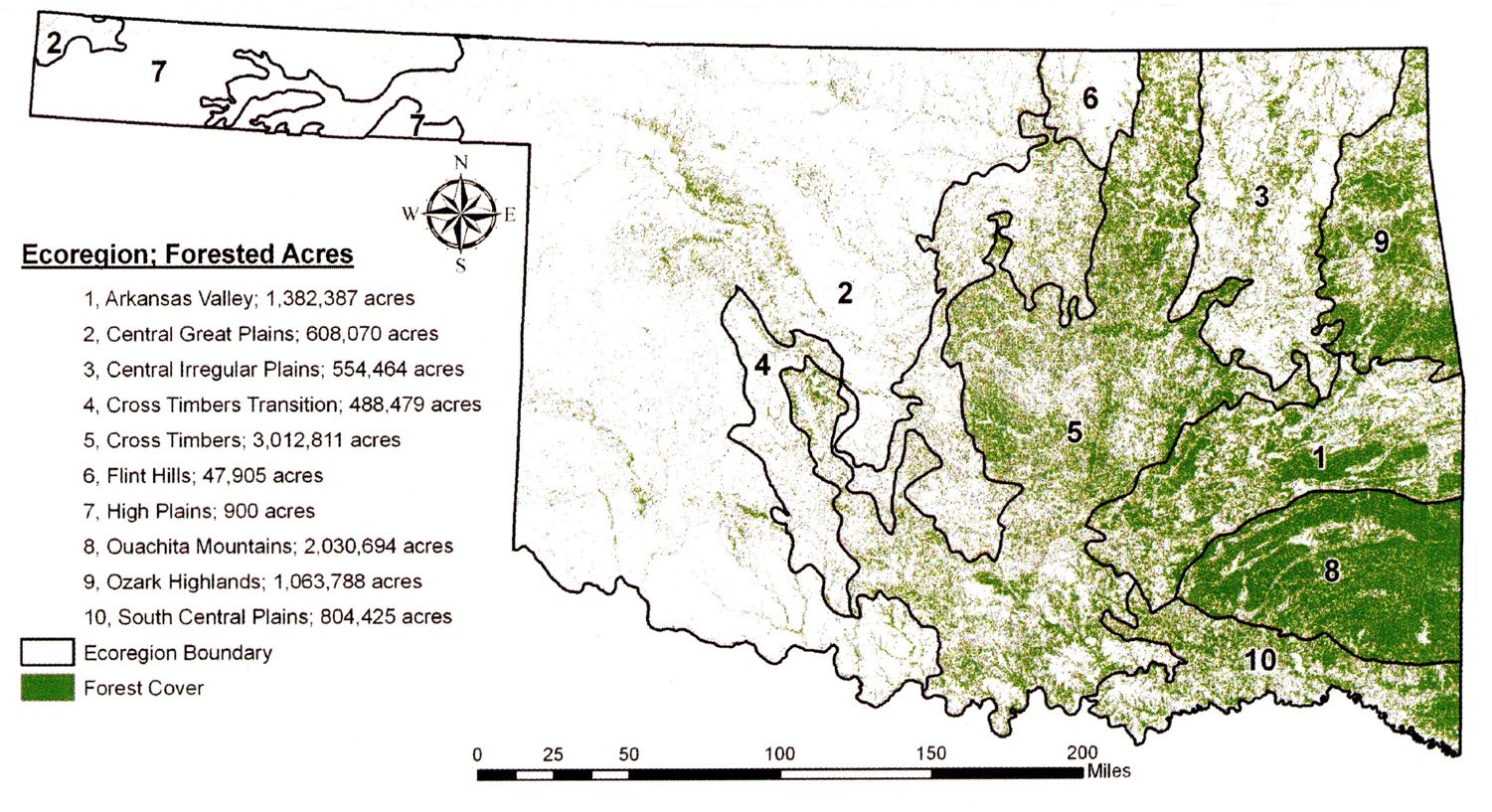

Figure 3 shows the actual area of forest cover within each of the ecoregions shown in Figure 2. The total area of actual forest region within Oklahoma comprises 10 million acres, or 22.3% of the total land area of Oklahoma (Table 3). Most of the forest cover is in the Arkansas Valley, Ouachita Mountains, South Central Plains, and Ozark Highlands regions. The percent of forested land within each of these 4 regions exceeds 40% with the highest occurring in the Ouachita Mountains ecoregion at 78.4%. About 90%, or 8.88 million acres, of the 10 million forested acres are privately-owned. The remaining forested area is owned by either the Federal government (754,000 acres), or state and local governments (326,000 acres; OFS 2010, page 55).

The portion of forested land in the Cross Timbers is 3 times greater than in the Cross Timbers Transition region (35.5 vs. 12.9 %). Both of these regions are considered generally as having non-commercial forests, except for small specialty markets. In addition, these regions are experiencing a dramatic increase in eastern redcedar (Juniperus virginiana) encroachment,largely due to the reduced frequency and intensity fires that occurred prior to the current era of fire exclusion that began in first half of the 20th century. Thus, some of the forested cover shown in Figure 3 in these two regions is likely attributed to eastern redcedar. The five ecoregions that are identified as either savanna or rangeland in Table 3 have <17 % woody cover. Wooded areas in these regions generally occur in the riparian channels.

Figure 3. Forest cover within Oklahoma ecoregions (from OFS, 2010, Oklahoma Forest Resource Assessment, page 37).

| Ecoregion | Land Typ | Total Acres | Forested Acres | % That is Forested |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arkansas Valley | Oak-Pine Forest | 3,077,680 | 1,382,387 | 44.9 |

| Ouachite Mountains | Oak-Pine Forest | 2,589,790 | 2,030,694 | 78.4 |

| South Central Plains | Oak-Pine Forest | 1,936,138 | 804,425 | 41.5 |

| Ozark Highlands | Oak-Hick Forest | 2,043,011 | 1,063,788 | 52.1 |

| Cross Timbers | Forest/Savanna | 8,487,831 | 3,012,811 | 35.5 |

| Cross Timbers Transition | Savanna | 3,776,350 | 488,479 | 12.9 |

| Central Irregular Plains | Savanna | 3,332,383 | 554,464 | 16.6 |

| Central Great Plains | Range | 16,632,500 | 608,070 | 3.7 |

| High Plains | Range | 2,251,529 | 900 | 0.04 |

| Flint Hills | Range | 617,230 | 47,905 | 3.7 |

| ALL | ALL | 44,744,442 | 9,993,923 | - |

| ALL | ALL | - | - | 22.3 |

According to 2012 estimates, the Oklahoma timber industry contributes over $4.5 billion in total economic contribution to the State’s economy each year, and provides about 6770 jobs with a net payroll of $352 million (Joshi 2017).

While forest industry is a major economic contributor to the state, the majority of

forest landowners are non-industrial private. There are over 8 million acres controlled

by over 115,000 family forest owners who have primary management objectives related

to wildlife habitat, recreation, aesthetics, fuels reduction, and maintaining ecosystem

function (Butler et al. 2016). The need to meet continued demands for timber, while

providing other forest amenities (water quality, wildlife habitat, recreational opportunities),

requires implementing state-of-the-art forest management strategies. To be most effective,

these strategies must be based upon a sound understanding of forest ecology that includes

knowledge of forest biology, taxonomy, ecophysiological process and management practices,

as well as the socio-economic forces such as market demand and landowner motivations

forest production and forest ecosystem health.

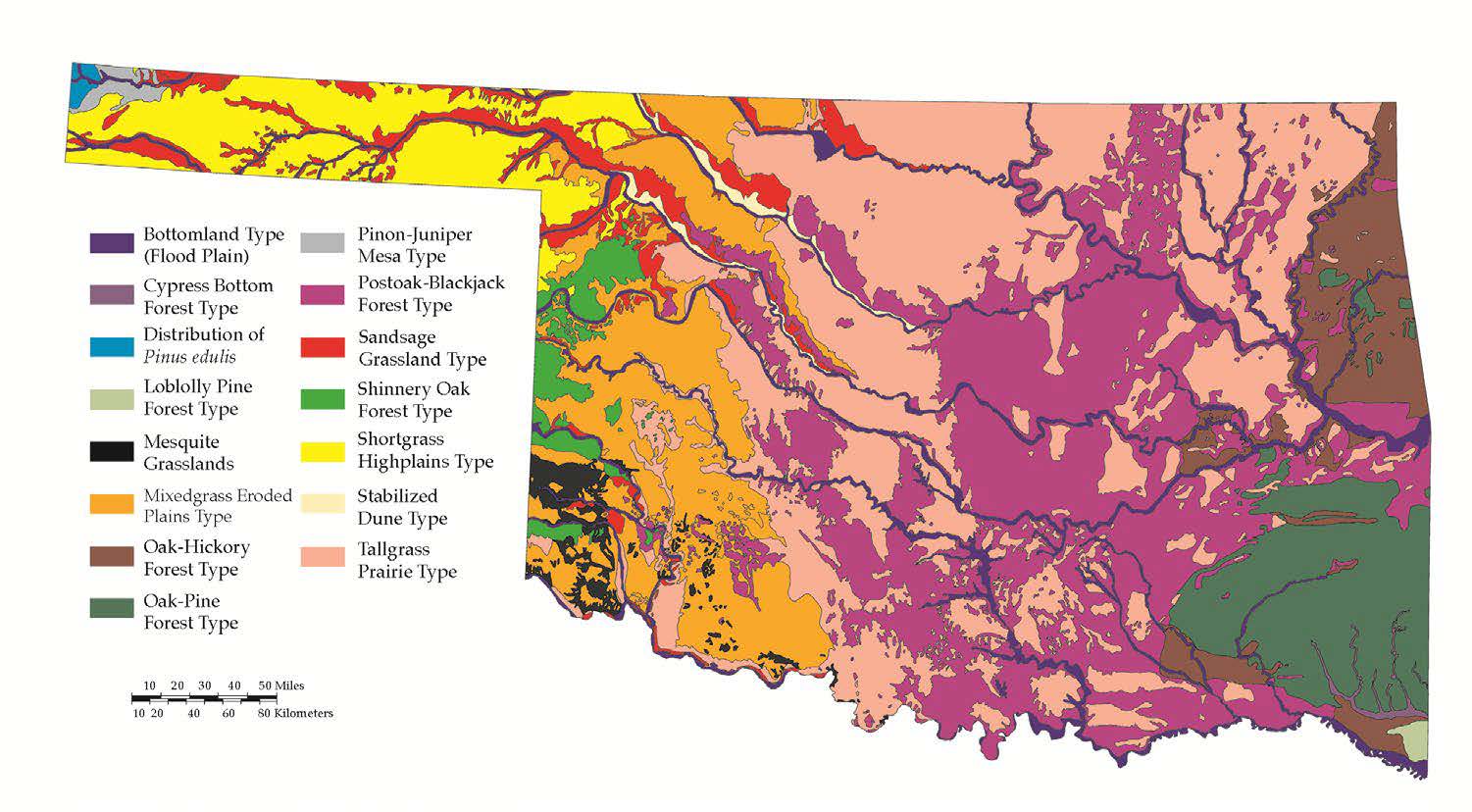

An Oklahoma vegetation map by Duck and Fletcher (1943) (Figure 4) reveals the great

diversity and complexity of vegetation regions across the state and points to the

need for an integration of natural resource disciplines to adequately address Oklahoma’s

natural resource needs.

Figure 4. Native vegetation regions in Oklahoma originally by Duck and Fletcher (1943), and as presented in Tyrl et al. (2008) Oklahoma’s Native Vegetation Types (Oklahoma State University extension publication E-993).

References:

Butler, B., et al. 2016. USDA Forest Service National Woodland Owner Survey: national, regional, and state statistics for family forest and woodland ownerships with 10+ acres, 2011-2013. Research Bulletin NRS-99. Newtown Square, PA: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Northern Research Station. 39 p. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2737/NRS-RB-99

Joshi, O. 2017. Economic importance of forestry in Oklahoma in 2012. Oklahoma Cooperative

Extension Service Publication. L-462. Oklahoma State University. 2 p.